For a decade, the TalkTech project has paired students from Bentley University in Waltham, MA, near Boston, USA, with students from Politehnica University of Timisoara, Romania, for an exploration of technology and culture across continents. Students must select and utilize appropriate web-based tools to communicate, collaborate, and create digital media artefacts that demonstrate their learning about current technology trends and developments. While the topics, preferred methods for communication, and deliverables have changed over the years to remain on the cutting edge of emerging technologies, the project’s basic premise has remained the same: to use information technology in ways that may have cultural or societal influences, and to create a context in which students must work effectively on a project with international partners. This paper presents a timeline of the TalkTech topics, lessons learned, and common themes during ten years of the TalkTech project.

1 Introduction

The ability to communicate internationally has evolved greatly over the past decade with the development and evolution of the Internet as a global communications platform, and the ubiquity of mobile devices. These developments have enabled communication by synchronous and asynchronous voice, text, and video messaging. Since 2008, the authors have been studying how university students living more than 4000 miles apart use web-based and mobile communication and collaboration tools by placing them as members of international teams tasked to explore current technology trends and deliver an original digital media product that reflects their learning.

Each academic year, the authors adapt the methodology and instructional design of the TalkTech project to reflect current technology trends and tools, creating a learning scenario where students can develop their own digital literacy (D. Andone & Frydenberg, 2014; Frydenberg & Andone, 2015, 2016) and 21st Century skills (Frydenberg & Andone, 2011). Since 2008, this project sought out Web 2.0 tools and mobile and web applications that were just beginning to find their way into educational settings (Frydenberg & Press, 2010). The TalkTech project’s objectives have remained to develop literacy skills through the simulation of a global work environment in which team members use web-based collaboration and communication tools to create digital content.

Over the years, the instructors analyzed the project through the lenses of computational thinking SAMR (Substitution/ Augmentation/ Modification/ Redefinition) Learning Model (Puentedura, 2014), 5-stages of e-tivities for active online learning (Salmon, 2002) connectivism learning (Siemens, 2014), digital literacy (Wheeler, 2012) and 21st Century Skills (Bell, 2011).

The original research questions from TalkTech 2008 (Frydenberg & Andone, 2010a) have guided this project since its inception:

- How does participating in an international collaborative environment for learning change students’ perspective over their subject of study (multimedia and internet technologies)?

- How will students use Web-based synchronous and asynchronous technologies to collaborate with international peers to create a tangible work product in a short amount of time?

- What technical and cultural challenges will students identify in working globally, and how will they overcome them?

2 TalkTech Implementation

The TalkTech project is a partnership between first year business students in IT 101, an introduction to technology concepts course at Bentley University, and Bachelor in Telecommunications engineering students in the Technologies of Multimedia (TMM) course in their final year at “Politehnica” University of Timisoara (UPT). Approximately 50-60 students participate each year, so more than 600 students have taken part in the project since its inception. All have completed it.

All students had some previous experience using the web, collaboration tools, and mobile devices. All students speak English. The Romanian students are typically three years older than the American students, due to the courses in which they are enrolled. Participants formed self-selected groups of four of five (two or three students from each country) collaborate with their international partners. The authors recognize that differences exist in age, programs of study, technical abilities, and class sizes of students at each university. For the purposes of this research, the authors welcomed these differences to design a learning project that encouraged collaboration among group participants.

3 TalkTech Timeline

The TalkTech project encouraged students to research emerging technologies and create digital content that reflected their learning.

3.1 The Early Years: TalkTech 2008, 2009

TalkTech 2008 and 2009 focused on communicating online with web-based tools. Students used instant messenger, skype, and mebeam to communicate. Topics included mobile phone apps of the future, dangers of social networks, how has the Internet changed the way we communicate. how do you use the WWW as part of your learning, important websites you should know, and privacy and social networking. The format of their final deliverables was left open to the students but could take the form a web page with images, a video, a PowerPoint, a recorded audio conversation, or a combination of any of these. Figure 1 shows a sample of student work.

Fig. 1. Sample presentations from TalkTech 2009 showing the future of mobile phone applications.

3.2 Moving to the Cloud: TalkTech 2010

TalkTech 2010 took place at the beginning of the move of desktop applications the cloud. Online collaboration became a new way of working together. Students tested, and reviewed web-based collaboration tools summarized in Table 1, many of which are no longer available or have been replaced with more current choices.

Table 1. Early Web-Based Collaboration Tools

| Presentations | 280slides and zohoslides | Video Conferencing | Dimdim, vyew | |

| Screen Sharing | Yuuguu, CrossLoop | Scheduling | Doodle, Meetingwizard | |

| Surveys | Google Forms, SurveyMonkey | Project Management | BaseCamp, Huddle | |

| Editing | Typewith.me, Google Docs | Note Taking | Protonotes, posti.ca | |

| Annotation | Diigo, evri | Image Editing | Picnik and sumopaint | |

| Brainstorming | Mindmeister, wridea |

The deliverables remained the same as in 2008, though the project moved from Google Sites to ViCaDis (Diana Andone & Vasiu, 2009), a new online learning environment developed and managed by UPT. ViCaDis provided teams with blogging and file sharing capabilities and enabled the instructors to monitor each team’s progress.

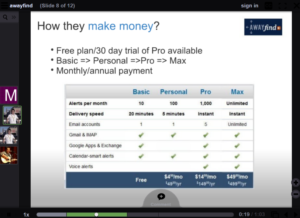

3.3 Web 2.0 and Entrepreneurship: TalkTech 2011, 2012

TalkTech 2011 and 2012 focused on Web 2.0 start-up companies. Students selected some of the newest and most promising Web 2.0 companies at the time, as identified at the O’Reilly Web 2.0 Expo Conference in New York City.(Wilson, 2011) They evaluated their products and services and created a collaborative online presentation that provided an overview of the company, its target audience and business model, and predicted its likelihood to succeed. Students also used screen recording tools to create a short video demonstration of their companies’ websites. To share their voice conversations and simulate presenting the slides together, students used VoiceThread, a collaborative platform for commenting on slide presentations, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. VoiceThread presentations from TalkTech 2011 and 2012.

3.4 Going Mobile: TalkTech 2013

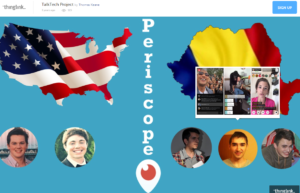

As more students started owning smartphones, TalkTech 2013 moved to the world of mobile devices. Students had to research and report on the most popular apps and websites for podcasts and blogs, travel, photo sharing, mapping, online payments, cloud storage, video streaming, and health and fitness.

ThingLink was the platform for sharing their collaborative findings, and created annotations using audio, video and text. Video annotations included short conversations between students from both countries about their topic. Text annotations included individual research that each student conducted about their topic.

3.5 Tech Trends and the Impact of Technology: TalkTech 2014, 2015

TechTalk 2014 focused on new technology trends. Students worked with their international partners to create ThingLinks in which they shared their findings on tech trends such as augmented reality, big data, internet of things, open data, wearable technology, 3d Printing, streaming video devices, digital currencies, MOOCs, mobile payments, crowd sourcing, and information privacy. In 2015, students examined the impact of these technologies in business, for example: how is augmented reality being used in healthcare, marketing, sales, or education; how does social media influence customer experiences; what are the biggest cybersecurity threats facing Internet users today; how does streaming audio and video impact the entertainment industry; how do mobile technologies and the Internet enable new business models through crowd sourcing; are MOOCs threatening the future of a traditional university education?

By 2015, Google Hangouts was relatively new and had promising features for group conversations and recording, though many students preferred Skype. Other popular tools of the time were YouTube’s video recorder, join.me, and a third-party video call recorder for Skype. Screen recording tools such as screenr and screencast-o-matic were new, and easy ways to create screen videos. The now defunct micro-video platform Vine was new at this time, and students used it to create short six-second videos to demonstrate or present their concepts creatively.

Fig. 3. A Vine video demonstrating Internet of Things, and a ThingLink on streaming from 2014 and 2015.

3.6 Augmented Reality: TalkTech 2016

TalkTech 2016 introduced Augmented Reality (AR), as advances in mobile technologies have enabled new forms of engagement through augmented reality apps in a variety of industries. Students created an augmented reality experience for their international partners and presented their group’s digital content using ThingLink. Students researched augmented reality creation tools such as Aurasma (now, HP Reveal), Blippar, and Layar to create AR experiences that were representative of the use of AR in healthcare, advertising, museums, education, interior design, training, mapping, sports, gaming, and tourism. This project, more than any of its predecessors, required the use of mobile devices. Students especially preferred them, rather than laptops, for communicating with their team members. Figure 4 shows a digital experience that one team created to demonstrate how AR might be used in the advertising industry. Scanning a Snapple iced tea bottle with the Blippar app displays links to the Snapple website, social media pages, and nutrition information.

Fig 4. AR Example for Advertising

3.7 Virtual Reality: TalkTech 2017

TalkTech 2017 promoted Virtual Reality (VR) and digital culture, as students created VR experiences using CoSpaces, a VR editing tool. Teams visited the same type of establishment in their countries (a coffee shop, library, public art installation, mobile phone store, museum, local landmark, sporting venue, etc), created 360-degree images, and annotated them with avatars and digital content. The deliverable was a demonstration video using Flipgrid, a video sharing platform, showing the results of researching an industry and its use of VR. Teams exchanged their VR artefacts and discussed cultural similarities and differences. Some groups used Google Cardboard viewers to experience their VR content. Figure 5 shows students’ visits to Starbucks coffee shops in Romania and in the United States.

a

b

c

Fig. 5. Starbucks Coffee Shop (a) in Romania, (b) in Google Cardboard, and (c) in the United States, created in CoSpaces VR

Students learned that business applications of VR will change how companies present and sell products and how customers will experience them, across several industries.

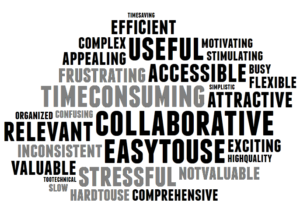

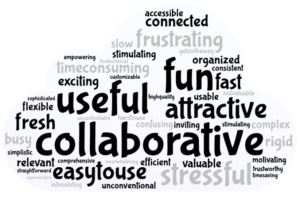

4 Desirability Test

Each year, to measure how desirable students found this experience, the authors followed a selection exercise developed by Benedek & Miner (2003) based on a set of 40 words, both positive and negative, covering a variety of dimensions. To account for any bias to give positive feedback, at least 40% of the words were negative. After the project, students selected five words that best describe their experience participating in this project. Students ranked the words they selected on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is the most precise. This method presents results visually in word clouds, from several of the TalkTech projects, as shown in Figure 6.

2008 2008 |

2011 2011 |

2014 2014 |

2017 2017 |

Fig. 6. TalkTech 2017 Desirability Word Clouds.

Students chose the words that appear in a larger font more frequently than words shown in smaller fonts. Of greatest interest is the term collaborative, which did not appear in the first iteration of the project but has been at the forefront of every word cloud in subsequent years. “TalkTech2008 was a social environment to share ideas with peers, see what others are doing and, as one student said, ‘give’ them ‘confidence that they are on the right track’ with their studies and understanding of technology.”(Frydenberg & Andone, 2010b, p. 11) Students found the tools to be accessible (the most popular word chosen in 2008), and as their use became commonplace, TalkTech evolved to include a collaborative project that students must complete.

In later years, collaborative became the predominant positive word, describing student involvements with collaboration tools and the opportunity to be a member of an international team. Frustrating remained one of the most commonly selected negative words, which often referred to difficulties of scheduling and interacting with team members due to time zone differences, and differing work styles. These word clouds hint at the evolution of the TalkTech project, which began as a way for students to access web-based communication tools at a time when these tools were new and morphed into a global collaborative work environment for investigating technology trends.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

As the TalkTech project requirements became more involved, completing them required using search engines, transferring files from one device to another, interacting with content in multiple file formats, navigating the Web, and learning basic coding concepts such as performing steps “in parallel”, looping, actions, and interacting with objects. Throughout the project years, students had to choose which tools they will use to interact with their partners from synchronous communication by voice and video conferencing to asynchronous chats and email; file sharing, multimedia creation, and project management.

The goal of earlier TalkTech projects was for students to evaluate and use tools for communicating and collaborating online, and the deliverables for the project were recorded snippets of voice or video conversations or screenshots of chat / messaging logs along with some form of digital media content. As students’ familiarity with these tools and apps increased, and as the tools and apps offered additional complex capabilities, the TalkTech project requirements became more challenging. Group messaging mobile apps, Skype, Google Drive, and Facebook pages became the collaboration tools of choice that students used to manage their group’s progress, replacing Yahoo! Messenger, Yahoo! Briefcase, email, and MeBeam, popular in the early years. Many students preferred their discussions using group messaging apps in real time rather than voice or video calls because they find texting more appealing than talking on the phone. Apps and tools for creating interactive annotated infographics, voice comments on slide presentations, videos, augmented and virtual reality artefacts have enabled more recent students to demonstrate their digital skills by creating much more complex digital media content than what their peers created during earlier years of the TalkTech project.

References

Andone, D., & Frydenberg, M. (2014). Developing Digital Literacy Skills through Interactive Images, Multimedia Mashups, and Global Groups. 2014 IEEE 14th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) (pp. 632–633). Retrieved September 9, 2018, from doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/ICALT.2014.184

Andone, Diana, & Vasiu, R. (2009). How a Virtual Campus for Digital Students (ViCaDiS) should be? (pp. 827–832). Presented at the E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education, Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved September 16, 2018, from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/32559/

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its place in theory-informed research and innovation in technology-enabled learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 98–118.

Benedek, J., & Miner, T. (2003). Measuring Desirability: New methods for evaluating desirability in a usability lab setting. Proceedings of Usability Professionals Association, 12 (Vol. 8, p. 57).

Frydenberg, M., & Andone, D. (2010a). Two Screens and an Ocean: Collaborating across Continents and Cultures with Web-Based Tools. ERIC Number: EJ1146778 Record Type: Journal Publication Date: 2010-Jul-21 Pages: 12 Abstractor: As Provided Reference Count: 16 ISBN: N/A ISSN: EISSN-1545-679X Two Screens and an Ocean: Collaborating across Continents and Cultures with Web-Based Tools Frydenberg, Mark; Andone, Diana Information Systems Education Journal, 8(55), 12.

Frydenberg, M., & Andone, D. (2010b). Two Screens and an Ocean: Collaborating across Continents and Cultures with Web-Based Tools. Information Systems Education Journal, 8(55), 12.

Frydenberg, M., & Andone, D. (2011). Learning for 21st Century Skills. Presented at the 2011 International Conference on Information Society, London: IEEE.

Frydenberg, M., & Andone, D. (2015). Social Media, Online Collaboration, and Mobile Devices: Tools for Demonstrating Digital Literacy. Proceedings of EdMedia 2015–World Conference on Educational Media and Technology. (pp. 6–15). Presented at the EdMedia, Montreal: AACE. Retrieved September 9, 2018, from http://www.learntechlib.org/j/EDMEDIA/v/2015/n/1/

Frydenberg, M., & Andone, D. (2016). Creating micro-videos to demonstrate technology learning and digital literacy. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 13(4), 261–273.

Frydenberg, M., & Press, L. (2010). From Computer Literacy to Web 2.0 Literacy: Teaching and Learning Information Technology Concepts Using Web 2.0 Tools. Information Systems Education Journal, 8(10). Retrieved September 15, 2018, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1146965

Puentedura, R. R. (2014). SAMR: A contextualized introduction. Retrieved from http://hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/01/15/SAMRABriefContextualizedIntroduction.pdf

Salmon, G. (2002). E-tivities: The key to active online learning. London: Routledge Falmer. Retrieved September 15, 2018, from http://daama.academia.iteso.mx/wp-content/uploads/sites/37/2014/09/Etivities_Salmon.pdf

Siemens, G. (2014). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. Retrieved September 16, 2018, from http://er.dut.ac.za/handle/123456789/69

Wheeler, S. (2012). Digital literacies for engagement in emerging online cultures. eLearn Center Research Paper Series, 0(5), 14–25.

Wilson, J. (2011, October 12). Startup Showcase: Web 2.0 Expo New York 2011 – O’Reilly Conferences, October 10 – 13, 2011, New York, NY. Retrieved September 14, 2018, from https://conferences.oreilly.com/webexny2011/public/schedule/detail/21067